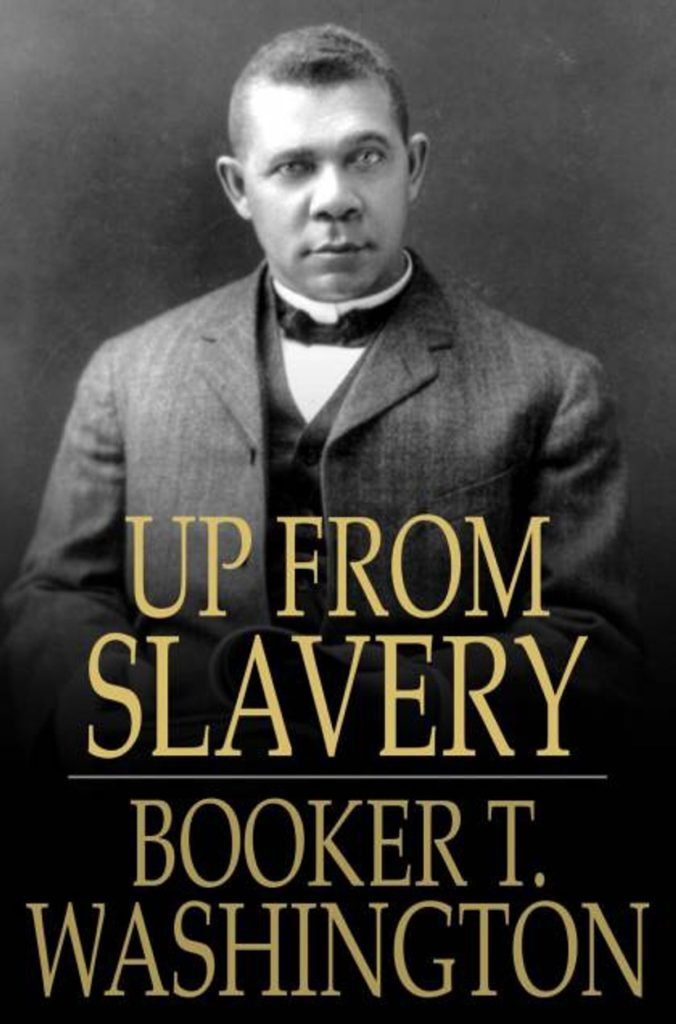

In 1901, Booker T. Washington wrote an autobiography, Up From Slavery. The book describes his position as a free black in the South, having to work his way up as a slave child (he was nine years old when the U.S. Civil War ended and the slaves were freed). I read this book via Audible and took notes using the app. As an Audible subscriber, the book was also offered at no extra cost, with a free credit, (perhaps Audible and Amazon’s way of responding to the Black Lives Matter movement).

Washington begins the book by proclaiming that blacks in America who went through slavery are equally or better off than any other blacks at any place on the globe. He added that the fact so many go back to Africa as missionaries show that so often Providence uses flawed men and institutions for a higher purpose.

Washington was clearly a Christian and in the book he talks about at a certain point in his life he began each day by reading the Bible, at least one chapter per day.

He saw the emancipation of slaves as one of the great challenges ever facing humankind. “The great responsibility of being free suddenly took possession of the freed slaves,” he said. “Within a few hours, the great questions that Anglo Saxons had been grappling with for centuries had to be solved [by free blacks]: questions of providing a home, a living, food, and churches.”

Washington says that now that they were in possession of it, “freedom was a more serious thing than they had expected to find.” In essence, while slavery is obviously hard (that’s an understatement), freedom isn’t easy – especially for a population that was never used to providing for themselves.

Freed blacks soon realized education was needed to better advance and there was much discussion among negros in his community in Virginia to open a school for the negro children but the biggest question was where to find a teacher.

Washington says that from early on, he had a determination to learn to read and there became a “great intensity among negros to learn to read, get an education, and read the Bible for themselves.”

His father recognized his financial value so he kept him working in the salt mines instead of school. But Washington was so determined to learn that he did night school which influenced his interest in promoting night school later on.

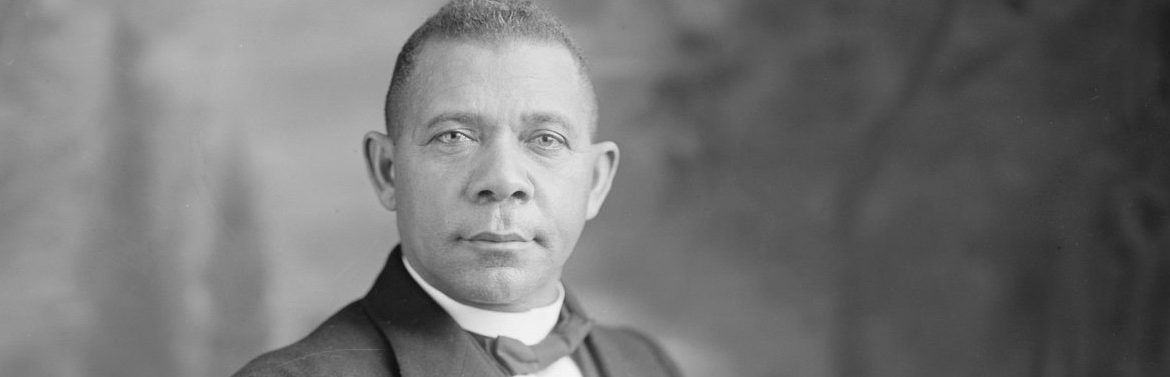

And now to his name. For most of his early life, he only knew one name: Booker. He said that when he was in class and the teacher called on him and asked him his full name he added: Washington. He later found out that his mom had given him the name of Taliaferro so he added it later as a middle name.

He said, In school, white children expected to succeed, while negro children expected to fail. However, he emphasized that, “Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles he has overcome while trying to succeed.”

He learned of the Hampton Institute in Virginia, a boarding school for negros where they could get expenses paid for and work for their boarding. He was accepted into it. He details that while on his travels there, through many Virginia towns, he finally learned what the color of his skin meant. In one story he details, he was not welcomed at a place of lodging on a cold Virginia night, because he was black.

From General Armstrong of the Hampton Institute, he learned that “No education that can be gained from books can equal that of contact with great men and women.”

“I have begun everything with the idea that I could succeed, and I never had much patience for the multitudes of people who are ready to explain why one cannot succeed,” said Washington.

He also “learned to love labor not just for the financial rewards but for labor’s sake and the self-reliance it brings.” He added that, “the happiest individuals are the ones who make others useful and happy.”

Washington also became a teacher, taught nights, weekends and Sunday school. He declined political service so he could focus on building a foundation for his race: education, industry, property.

“How often I have wanted to say to white students that they lift themselves up in proportion to how they lift others up,” said Washington.

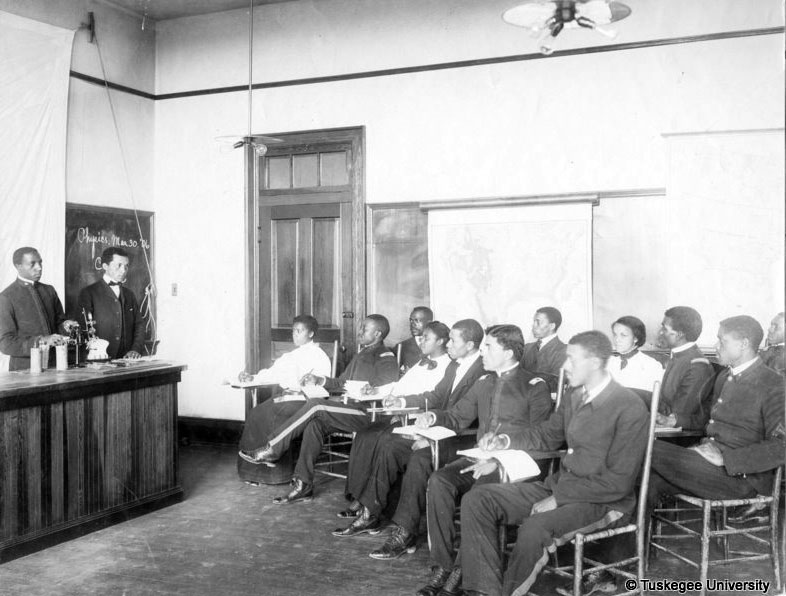

He was part of the founding of the Tuskegee Institute in 1881, a normal school for blacks in Tuskegee, Alabama. He was hired as the principal there in its first year. He said that most students wanted to get an education so they would no longer have to work with their hands.

He also detailed how so many of the older blacks in the community, among many others, did everything they could to help the school. One older former slave woman donated six eggs to the Tuskegee Institute. “Tuskegee has many who are friends in Alabama and in the South,” he said.

Washington details how he taught students the value of labor by having them participate in building the school buildings. The students learned the trade of brickmaking, which was used for the buildings and they also sold bricks.

“I have found that there is something in the human being that rewards and recognizes merit no matter the race,” said Washington. “The white man who begins by cheating usually ends by cheating a white man.”

The book is also full of so many little tidbits he learned along the way, including hygiene and his “gospel of the toothbrush.” He added that he believes in keeping the body in good condition. “If you take care of the little ills the big ills will not come.”

Also, public speaking and fundraising. Colonel Armstrong gave him advice for public speaking: “give them an idea for every word.” Two rules which he learned that he recommends people in philanthropic causes remember: “always make your cause known to individuals and organizations, and don’t worry about the results.”

He also gives good life advice: “Worrying only consumes and to no purpose … physical and mental strength that might otherwise be given to effective work.”

“When one takes a survey of the country and the people in it you find that the most interesting and best people are the ones that take more of an interest in helping people and causes that make the world better,” he says. He was also encouraged that “the world is growing in the direction of giving.”

“The money didn’t come to Tuskegee because of luck. It was hard work,” he said. “Nothing worth anything doesn’t come for any reason other than through hard work.”

Washington recounts that a large donation they received from Andrew Carnegie to build a library took 10 years from the time he first met him.

He also explains that the Tuskegee Institute is nondenominational but thoroughly Christian. “It is a hard matter to convert an individual by abusing him,” he says. He really believed highly in persuasion and example.

Booker T. Washington was invited to give an address in Atlanta on Sept 18, 1895. His reception there gave him more national recognition. He mentioned how much trepidation he had before it because he had a “mixed audience” when he “prefers to tailor his message to particular audiences to reach their hearts.”

On self-education and experience, Washington asserts that “In my contact with people, I find that, as a rule, it is only the little, narrow people who live for themselves, who never read good books, who do not travel, who never open up their souls in a way to permit them to come into contact with other souls – with the great outside world.”

He adds: “I have found the happiest people are those who do the most for others, the most miserable are those who do the least.”

On voting, he mentions that the ballot should be protected in the South but whatever test required they should apply with equal justice and to both races. By the time he wrote this book, published in 1901, he had found that the race in the South was improving materially, educationally, morally.

As a man who believed so strongly in helping himself and others be self-reliant, he states that “there is absolute joy and fulfillment of being the master of one’s work.”

He was also a seriously hard worker and only took one vacation in 19 years – he and Mrs Washington spent 3 years in Europe.

Washington was an avid reader and mentions that the kind of books he enjoys the most are biography. He claims to have read almost everything written about Abraham Lincoln.

“I believe that any man will be filled with constant unexpected encouragements of this kind if he makes up his mind each day to do his level best each day of his life, that is tries to make each day reach as nearly as possible the high water mark of pure, unselfish, useful living.”

Washington received an honorary degree from Harvard, and on December 16, 1897, President McKinley visited the Tuskegee Institute, bringing much excitement from everyone in the town.

Washington concludes the book by proclaiming that “The great human law that recognizes and rewards human merit is everlasting and universal.” He adds that, “The outside world does not know and can’t understand the struggle that goes on in the hearts of Southern white men and their former slaves to free themselves from racial prejudice. And while both races are thus struggling, they should have the sympathy, support, and forbearance of the rest of the world.”

Most importantly this book paints a picture of a man who did not make excuses, but tried to move himself forward every day, taking every opportunity for self-education towards a path of self-sufficiency. And, as a teacher of others, trying to do his best to help his fellow former slaves and descendents of slaves, to take it upon themselves to move their race forward, while also finding allies and sympathy with Southern whites who were also wrestling with a new paradigm upon which they found themselves. This is an exceptional autobiography by one of the most exceptional men in American history.