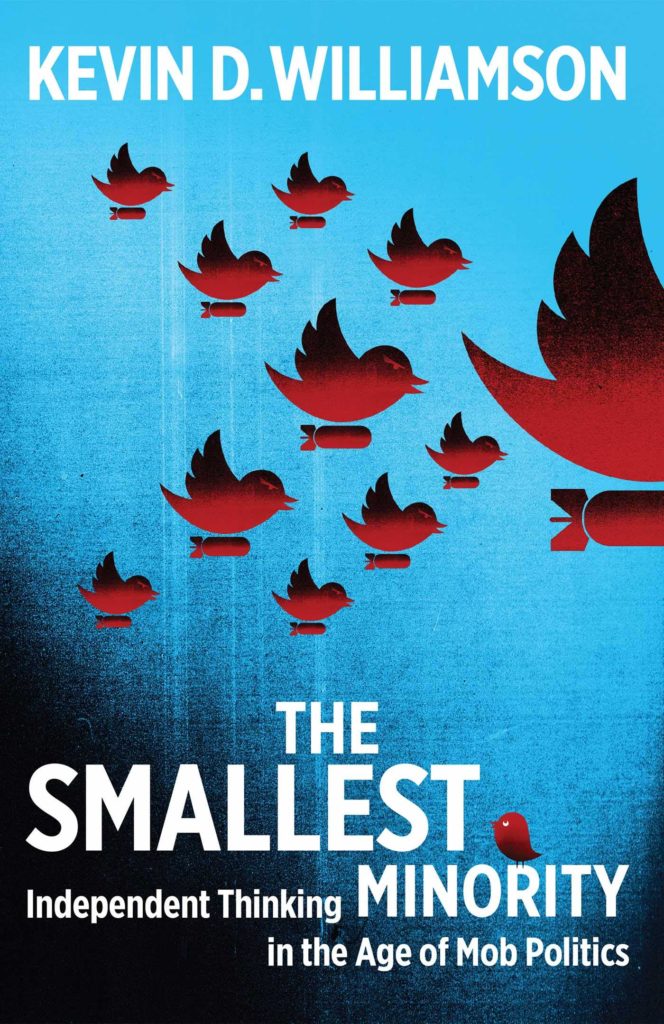

“The original sin of the American intellectual is his desire to be popular.” That is clearly not one of the sins probably ever committed by Kevin Williamson, a National Review Institute fellow and author of the new book, The Smallest Minority: Independent Thinking in the Age of Mob Politics.

We now live in an era where “everyone is a public figure,” says Williamson. Why? Because everyone is connected or associated to something. And the mob is in constant outrage against almost everything. It doesn’t matter where you fall on the political spectrum, you can be targeted by mob politics, which isn’t new. It extends thousands of years back into history. It is, after all, why our founders created a Republic, and not a democracy. They cautioned against the mob. However, today, mob politics takes a new form of insanity with the advent of the internet, 24/7 cable news, and social media.

“Social-media mobs provide a partial substitute for the sense of identity and belonging that disruptive global capitalism has taken away from many people,” says Williamson.

“We think in language. We signal in memes. Language is the instrument of discourse. Memes are the instrument of antidiscourse,” he says. “The function of discourse is to know other minds and to have them know you; the function of antidiscourse is to lower the status of rivals and enemies.” As someone who has sent my share of politically driven memes to friends, I concur.

In our modern-day democracy, we have abandoned individuality for group identity. “Groups do not think in any meaningful sense. People think – one at a time. And they exchange thoughts.”

The demands of tribalism are “debasing and squandering the only asset this country – this world – has: the functioning individual mind,” says Williamson. “Genuine political discourse and political culture are possible only among those individuals with enough regard for their own individuality and sufficient confidence in its value to stand apart from the tribe, however partially or imperfectly, and say what needs saying.”

“We need free minds now more than ever,” says Williamson. He has a great chapter about the individual and the corporation and how corporations, all organizations really, are more scared of the mob than ever. They bend and cow tow to it.

He has another chapter on the constant social media cage matches. “Social-media users are lonely, isolated, and in search of significance. They seek to associate themselves with people who are significant.”

There’s yet another chapter on status and signaling. “As long as I was at National Review and as long as Bret Stephens and Bari Weiss were at the Wall Street Journal, we were only ordinary players in the antidiscourse game: rivals, to be sure, but rivals who knew our places. Affiliation with the organizations that the Left regards as its own private status preserve is what rendered us intolerable. The status shift, and not anything having to do with our work itself, is what aroused the mob.” [Kevin Williamson was hired and quickly fired by The Atlantic magazine and Bret Stephens and Bari Weiss went on to The New York Times, all under fire by the hysterics of the mob].

For someone like Williamson who, on his first days at The Atlantic magazine faced a similar mob, he says he will be fine. A writer, like himself, who invites controversy through his writing – that’s his job. But the average individual – whose job this is not to be involved in controversy for a living – can now be affected by it and become a victim to the mob, at almost any moment. The examples are endless, but the Convington kids with the MAGA hats come to mind. Not only were they targeted, but their parents and the businesses their parents worked for.

Williamson says, “there is no such thing as principled censorship” and has a chapter dedicated to free speech and true tolerance. He gives many examples in our current day where speech is now being classified as violence in the name of public safety. “From the point of view of scandal, the fact that certain ideas and opinions are expressed at all is evil in and of itself, and that they may be expressed in public without several legal or social sanction is an evil of an even more expansive character because the example contributes to the corruption of public morals – the crime for which Socrates was given the hemlock.”

For progressives, “the bigger the mass the better – and, by implication, the smaller the minority, the worse for its members.”

In the afterword, Williamson warns that “mob rule does not end with the mob,” and warns of a coming American Police State, which is “what happens when the mob successfully recruits the state to act as its henchman.”

“What the mob hates above all is the individual, insisting on his own mind, his own morals, and his own priorities. The mob hates him less for the content of his views than for the fact that he holds them without the mob’s permission and declines to abandon them at the mob’s demand. Democracy has always been the enemy of minority rights. It always will be. And the biggest democracies will always be a dangerous place for the smallest minority.”

This book is a great reminder why turning off cable news has been a great idea for me over the past two years. I actually read more; I also try to read from many sources and read things that challenge me. This book did just that and gave me a lot to contemplate. And, as you being to understand Kevin Williamson’s humor, you often laugh out loud on almost every page, especially when you read the very creative footnotes, which are often ramblings on various thoughts he probably had as he was putting words down. There are few better writers in American than Kevin Williamson. Just know you are bound not to agree with much of what he says. And I’m sure he’s just fine with that, as long as you are fine with giving him the freedom to express it. Sadly, that was not a task The Atlantic magazine was comfortable defending. And there’s an entertaining chapter about that too.