I recently completed reading The Wright Brothers by historian David McCullough. He has written many prominent books on historical figures, most notably his work on John Adams. He published The Wright Brothers in 2015 and I listened to the audio version of the book via Audible, which has a feature that enables you to clip audio and take notes in the app. This allowed me to put together more of a synopsis of the book, including recapping some of the important takeaways I had which I’ve written below.

As McCullough notes, by the time that the Wright Brothers had invented a flying machine, the state of Ohio had already produced three Presidents plus another famous inventor: Thomas Edison. He cites William Dean Howell of The Atlantic Monthly, who points out that “the people of Ohio were the sort of idealists who had the courage of their dreams.”

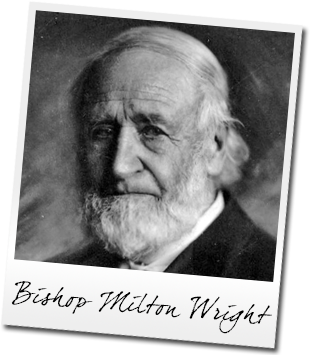

Wilbur Wright was an outstanding student and possibly on his way to Yale, but that ended when he was playing hockey on the lake and had his front teeth knocked out by a neighborhood bully (that bully who went on to become one of Ohio’s worst murderers). Wilbur became a recluse for the next three years, but that was when he began reading as never before. The Wright family had a large book collection. Their father, Bishop Wright, preferred informal education at home over formal education at school. Wilbur read just about everything but especially loved history.

His brother, Orville Wright, later said that “It isn’t true to say we had no special advantages. The greatest thing in our favor was growing up in a family where there was always much encouragement to intellectual curiosity.”

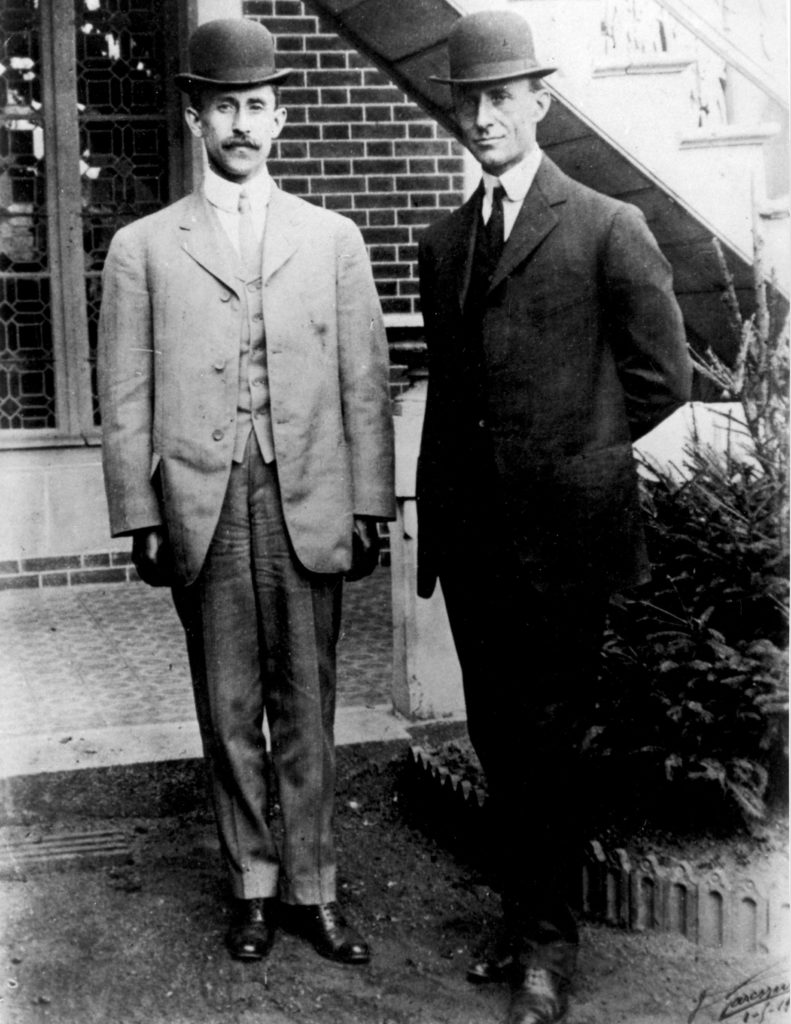

The brothers were also very entrepreneurial. Orville had an apprenticeship with a locomotive print shop and then his own small printing press. In the 1890s, bicycles became very popular and were “all the rage” across America. In the spring of 1893, Wilbur and Orville opened their own bicycling business, the Wright Cycle Exchange, selling and repairing bicycles. They later renamed it the Wright Cycle Company.

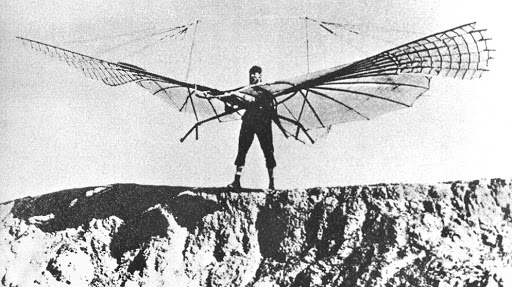

There were many exciting developments in the late nineteenth century. Wilbur and Orville had also been following the German glider enthusiast Otto Lilienthal who found that the secret of flight was having wings like a bird. It was also during this time that Wilbur turned a lot of his reading toward aeronautics and flying.

According to McCullough, on March 30, 1899, Wilbur wrote one of the most important letters of his life, and perhaps one of the most important letters in history, to the Smithsonian Institution. He asked them if they could make any books or papers available to him on the mechanical information related to flight because he thought manned flight was possible. They responded by sending him some papers and he and Orville consumed reading them.

During this time, Dayton, Ohio, where they lived, was a city where there was an ever-present atmosphere of inventing things. The U.S. patent office ranked Dayton as the number one place (relative to population) in the creation of new patents in America.

After studying people like Lilienthal and Bouard, the brothers gained an unquenchable enthusiasm to solve the problem of flight. Their studies led them to believe that equilibrium was the biggest challenge that needed to be solved. The trick was not getting into the air, but staying there. They knew wind was the greatest factor and they believed they needed to go to a place where they could practice over and over and get to know the wind. They studied records from the Smithsonian about wind velocity in all different places around the country. This led them to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Kitty Hawk was 700 miles from Dayton and the furthest place either of them had ever been. It also provided them a place of experimentation that could be carried out with privacy.

Throughout their flight experimentation, McCullough tells us they were there to learn, not to take chances for thrills. “The man that wishes to keep at the problem long enough to really learn anything positively must not take dangerous risks. Carelessness and overconfidence are generally more dangerous than deliberately accepted risks.” Caution and careful attention would be the rule for the brothers. They would take risks, but only when absolutely necessary.

They also spent some of their time on the beach in North Carolina watching seagulls take flight. Some of the locals thought they were a couple of nut balls, imitating the bird movements.

After nearly four years of concentrated study by the brothers, October 19, 1900, “proved a day of days,” said McCullough. Wilbur made one manned flight after another. It’s not known how many. Some heights and speeds were recorded, but not all. They returned to Dayton and then went back to Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina in July 1901, only to encounter a huge mosquito problem. This sidelined them for about a month.

In August 1901, they were back in the air but their wind warping since was not working as planned. During this time, aviation pioneer Octave Chanute came to visit Kitty Hawk and observe the Wright Brothers. After a few days he was convinced the Wright Brothers had made more progress than anyone before and urged them to keep at their work.

However, on their return trip back to Dayton, they were as down as ever, mostly because they discovered through their experiments that the data and equations recorded by others ahead of them, ones they studied with diligence for so long, had proven to be wrong and could no longer be trusted. Clearly those accepted authorities had been guessing, grasping in the dark, and those previously accepted tables they had spent so much time studying had been proven to be worthless.

The ingenuity and patience that the Wright Brothers had brought to their experiments was more than anyone before them. Back in Dayton, they built a wind tunnel in their bicycle shop, to keep at their aeronautic investigations. Over nearly two months, they tested 38 wing surfaces. It was a slow, tedious process.

Later, a British aeronautical journal would describe their efforts this way: “Never in the history of the world had men studied the problem with such scientific skill nor with such undaunted courage.”

Chanute kept offering them funding so they could devote all their time to their experiments, but they were unwilling to accept it. They used the funds made from their bicycle shop to keep their experiments going. They said their biggest cost was the time away from their bicycle shop. They had done everything on their own, paying their own way, and they intended to keep going on their own.

By the end of 1902, they had acquired the skill to fly. They could rise and float. They now just needed to build a motor. And that’s what they set out to do.

In the fall of 1903, they continued to run experiments at Kitty Hawk and installed the engine they had built for their glider. They encountered rough weather, but when it improved they went right back to work.

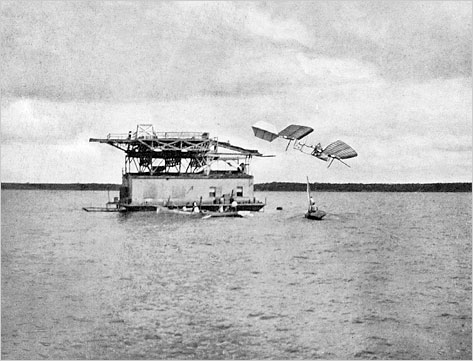

Meanwhile, in Washington DC, the government-funded flight experiment made by Samuel Langley failed. The attempted flight plunged into the Potomac without getting more than 20 feet off the ground. Over a decade of research and an undisclosed amount of public money caused the Washington Post to declare the government’s experiment a waste of taxpayer money.

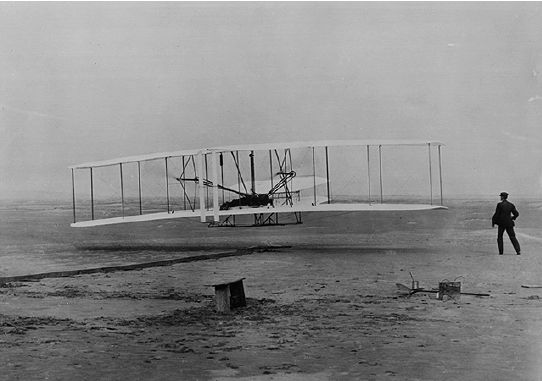

Back at Kitty Hawk, on December 17, 1903, the Wright Brothers achieved flight for about 12 seconds and 120 yards. Orville took the first flight, then Wilbur took a turn, then Orville went again. Wilbur flew about a half-mile during a time of about 59 seconds.

“It had taken four years,” said McCullough. “They had endured violent storms, accidents, one disappointment after another, public indifference or ridicule, and clouds of demon mosquitos. To get to and from their testing ground, they had made five round trips from Dayton … a total of 7,000 miles by train, all to fly a little more than a half a mile. No matter. They had done it.”

Their flights on that morning of December 17 were the first ever in which a piloted machine took off under its own power into the air, in full flight, sailed forward with no loss of speed, and landed at a point as high at which it started.

While the failed Langley project cost over $70,000 of taxpayer money, the Wright Brothers’ total cost over four years was $1,000, including all their travel expenses from Ohio to North Carolina, a sum paid by their modest bicycle store profits.

“It wasn’t luck that made them fly – it was hard work and common sense,” said John T. Daniels, one of the witnesses at Kill Devil Hills. “They put their whole heart and soul and all their energy into an idea and they had the faith.”

The brothers returned to Dayton believing they had mastered the problem of mechanical flying. However, they knew they had much more to do. The flyer that flew that day at Kitty Hawk in 1903 returned to Dayton with them and would never fly again.

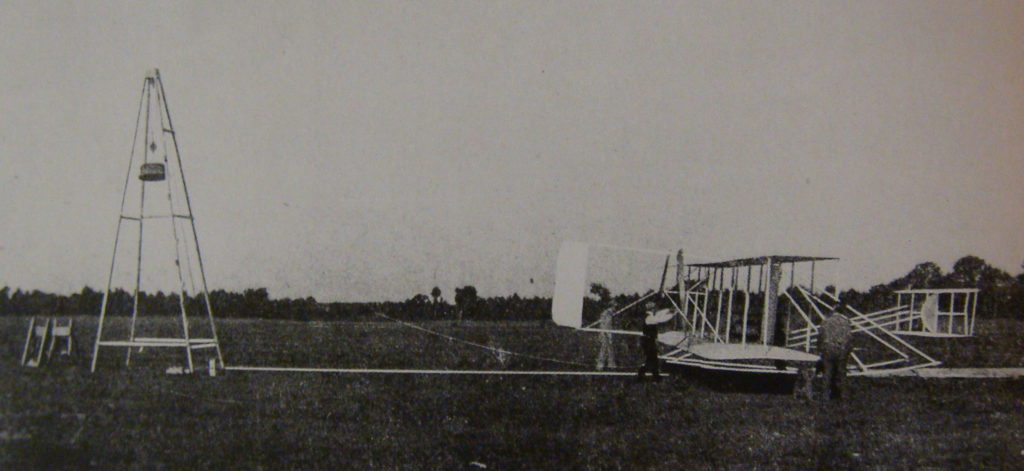

They built a new machine and flew it at Huffman Prairie, on the outskirts of Dayton, Ohio, in the summer of 1904. During the next summer and fall of 1905, also in Huffman Prairie is where the brothers truly learned to fly – in Flyer III. In some flights they went as far as 10 to 15 miles. On one afternoon on October 5, 1905, before about a dozen witnesses, Wilbur circled the prairie 29 times, landing only when his gas ran out.

The brothers had made over 105 starts at Huffman Prairie and thought it was now time to put their creation, Flyer III, on the market. The U.S. government did not yet seem interested. A Frenchman offered them $200,000 for the flyer and sent them a $5,000 deposit before the negotiations were even to start. The $5,000 was more than they had spent in total on all of their experiments.

A French businessman came to visit the Wrights in Dayton. No agreement was reached, but the French were convinced of the Wrights’ flying machine. At that point, many more press started becoming interested and began reporting on the Wrights’ flying machine. Later, a Frenchman flew a plane over 700 feet in the air. This did not pose a threat to the Wrights. They knew how much further he and others had to catch their progress. The Wrights began talking to the Flint company about producing and selling their flyer.

In 1907, Wilbur took a trip to France to engage in talks to make sales of their plane. While there, he took in all the city had to offer. He spent much time at the Louvre and was impressed by art, architecture, and the city, including the boulevard and cafes. When approached by media, he kept his answers brief. Some met him and the Wrights’ flying machine with skepticism. While in France, Wilbur observed a hot air balloon festival and took his first ever hot air balloon ride. About 3-4 times per week, he wrote letters back to his family and to keep Orville up to date with how business was going.

Wilbur was there for about two months. It was at that point that Orville joined him. They met with the Flint company executives and expressed they would not be selling any part of their patent or company; they merely wanted the Flint company to be their sales agent. At the tail end of their trip in 1907, the French seemed convinced that their own French flyers and country were ahead in the aviation race, so they did not purchase the Wrights’ flyer.

Upon their return to the U.S., the Wrights made some headway with the U.S. Army. In February 1908, the War Department contracted with them for $25,000 for their flyer. In March, they signed an agreement with a French company, with an understanding that the public demonstrations of the flyer would take place in France in midsummer.

The brothers went back to Kitty Hawk for more flying experiments – neither had flown in two years. And now, they had to deal with an invasive press in their lives, one that would dominate their space forever after.

McCullough cites a writer from Collier’s Weekly, Arthur Ruhl, who described Kill Devil Hills and Kitty Hawk, a very barren place, as the end of the world. However, at this point, Ruhl said, it had in fact become the center of the world “because it was a touchable embodiment of an idea, which presently has been to make the world something different than it ever was before.” It was a photographer for Collier’s Weekly, James Hare, who snapped the first photograph of the Wright Brothers flyer in the air.

By the summer of 1908, the brothers had become popular figures, dazzling the public imagination. But there still had not been a major public demonstration. “The rabbit had still to be pulled from the hat for all to see,” said McCullough.

In August 1908, Wilbur flew the flyer in a public demonstration at Le Mans, France, flying for two minutes. McCullough notes that it was here that “he proved the skeptics wrong and signaled that a new age had begun.” Two days later he flew again, making a figure 8 and landing the plane in the exact spot he took off from. Wilbur demonstrated how much control he had flying the machine. On August 13, he flew again, but this time he crashed the left wing into the ground while trying to compensate for flying too low. The admiration of the crowd did not diminish. He even impressed some.

Across the pond, back in the United States, Orville flew at Fort Myer, Virginia. On September 9, 1908, he flew in 55 circles for 1 hour and 3 minutes, a new world record. The next day, he flew even longer. On that day, September 10, Gutzon Borglum, the future sculptor of Mount Rushmore, was there. He wasn’t terribly impressed. To him, it looked simple. In his time flying at Fort Myer in September 1908, Orville had set seven world records. President Teddy Roosevelt was so excited by this he announced his intention to fly in Orville’s plane with him. Orville said he wouldn’t turn the President down but he didn’t believe the President of the United States should take such chances.

Just a few days later, September 17, 1908, in front of a crowd of over 2,600 people, with Lt. Selfridge of the appraisal board with him, the plane crashed. Orville was in critical condition, with a fractured leg and hip and four broken ribs. He survived. Lt. Selfridge had died. After an investigation, the cause of the crash was identified. One of the blades of the propeller had cracked, causing the propeller to vibrate, which tore lose a stray wire, which had wrapped around the blade. The broken blade had flown off into the air and the machine went out of control. While each of the Wright Brothers had crashed a few times before, this was the first time anything had broken on the plane to cause a crash.

Their sister Katharine came to DC to tend to Orville by his bedside. After five weeks, he was released and was placed on a train to Dayton, heading home with his sister who had taken time off from her own work to be with him in DC.

Back in France, Wilbur set another flying record, with over 1 hour, 32 minutes in the air and flying over 40 miles. The U.S. ambassador to France was in the crowd and was the first to congratulate Wilbur on his achievement. “Not since Benjamin Franklin had any America been so overwhelmingly popular in France,” said McCullough. As said by the Paris correspondent to the Washington Post, “It was not just his feats in the air that aroused such interest, but his strong individuality. He was seen as a personification of the Plymouth Rock spirit, to which French students of the United States from the time of Alexis de Tocqueville had attributed the grit and indominable spirit that characterized American efforts in every department of activity.”

In a speech thanking the people of France, Wilbur said, “It is not really necessary to look too far into the future. We see enough already to be certain that it will be magnificent. Only let us hurry and open the roads.”

On December 31, 1908, Wilbur flew 2 hours, 20 minutes, covering a distance of 77 miles – the longest distance anyone had ever flown. He won the Michelin Cup. Wilbur flew many demonstrations for crowds in France, near Pau, over the Pyrenees mountains. His sister Katharine was there for those demonstrations and even went up and flew with him a few times, getting the opportunity to take in magnificent views.

The Aero Club of America presented the brothers with a gold medal upon their return and Congress voted that a medal be presented to them by President William Howard Taft.

Back from his injuries, Orville flew again at Fort Myer on July 27, 1909. On another day, he broke another world record. In 1 hour and 12 minutes, he flew around the field 79 times at an altitude of 150 feet, with 8,000 in attendance, including President Taft. After Orville flew a successful series of flights at Fort Myer, the War Department awarded them with an investment in their aircraft. Their own country was finally committed to their achievement.

It has been a long journey, and while they admitted they had not conquered the air entirely, they started the way forward over many years dedicated to doing so. “A man who works for the immediate present and its immediate rewards is nothing but a fool,” said Wilbur Wright.

By August 1909, 22 pilots competed at Le Mans, and many flying records were broken. Also, that year, Wilbur flew over the Hudson River, where crowds at Battery Park and on the Lusitania cheered him on. He even circled the Statue of Liberty. Wilbur also went down to College Park, Maryland to train Army pilots.

On May 25, 1910, Orville flew in Dayton in a spectacular air show. He grazed the ground, he shot up like an arrow, he did figure eights in the air, and he climbed up to an astonishing altitude of 2,750 feet. Interestingly, from the very beginning, the brothers had agreed never to fly together, that way if one was killed in an accident, the other could continue with the work. However, on May 25, 1910, they flew together in the same plane for the first and only time. As McCullough points out, many believed it was their way of saying they had accomplished everything they set out to do. Also, on that same day, Orville took their father up in the plane. He had never flown before. Now, at age 82, Bishop Wright become the oldest person thus far to fly. His only words to Orville, once in flight was: “Higher, Orville, higher.”

Wilbur died of typhoid fever in 1912, at the age of 45. Neither he nor Orville ever married. Orville lived until 1848 (age 76). He lived long enough to see the horrors of WWII, including the role of aircraft in participating in that horror. But he also lived long enough to see the rocket and the breaking of the sound barrier.

While Orville was still alive, in 1928, the Smithsonian said: “To the Wrights belongs the credit of making the first successful flight with the heavier than air machine carrying a man.” But it would be another twenty years for the Wrights’ 1903 Flyer to travel from England back to the United States and be presented to the Smithsonian for display. And by then, Orville was no longer alive.

After Charles Lindbergh made his flight from New York to Paris in 1927 – once thought impossible by the Wright Brothers – he came to Dayton to pay his respects to Orville. And, on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong – another American from southwest Ohio – stepped onto the moon, he carried with him a small swatch of the muslin from a wing of their 1903 Flyer.

When reading the story of the Wright Brothers and reviewing the details, their hard work, their patience, their focus, it is just an astonishing thing to ponder. They are examples of perhaps the greatest achievement not just of flying, not just of the American spirit, but of the spirit of innovation. It is worth repeating a line above that Wilbur Wright once said, “A man who works for the immediate present and its immediate rewards is nothing but a fool.”

They didn’t do this for pride, they didn’t do this for glory, they didn’t do this to win a prize. They did this because they believed it could be done and they went at the work of doing it, no matter the length of time or effort or cost it was going to take them. Perhaps the only pride they had was the good old-fashioned pride of funding it themselves. Today, as flights take off and land thousands of time every day and in almost every geographic spot across the planet, we take for granted that it was only barely over a century ago that people mocked those who believed that man could one day create a flying machine. We must always remember the hard work ethic and magnificent patience that Wilbur and Orville Wright had to get us to where we are today. Greats like Charles Lindbergh and Neil Armstrong never forgot – and neither should we. Let us continue to take flight!